藤壺的幼體形態「腺介幼體」,是孔寬楯藤壺得以定居火珊瑚的關鍵。

圖|研之有物(資料來源:陳國勤)

當你漫步在臺灣岩岸的海邊,可以看到岩石上有許多長得像小火山的藤壺,牠們的本體藏在堅硬的外殼底下,在覓食時會伸出「蔓足」抓取海中浮游生物。或許外表看不出來,但是牠們跟螃蟹、蝦子同屬節肢動物的甲殼類。

藤壺形態各異,不只那些長得像火山的「笠藤壺」,還有形似龜爪或鵝頸的藤壺,有興趣可以參考這篇「無所不在的藤壺:與珊瑚共生的低調房客,也是操控螃蟹的蟹奴!」。

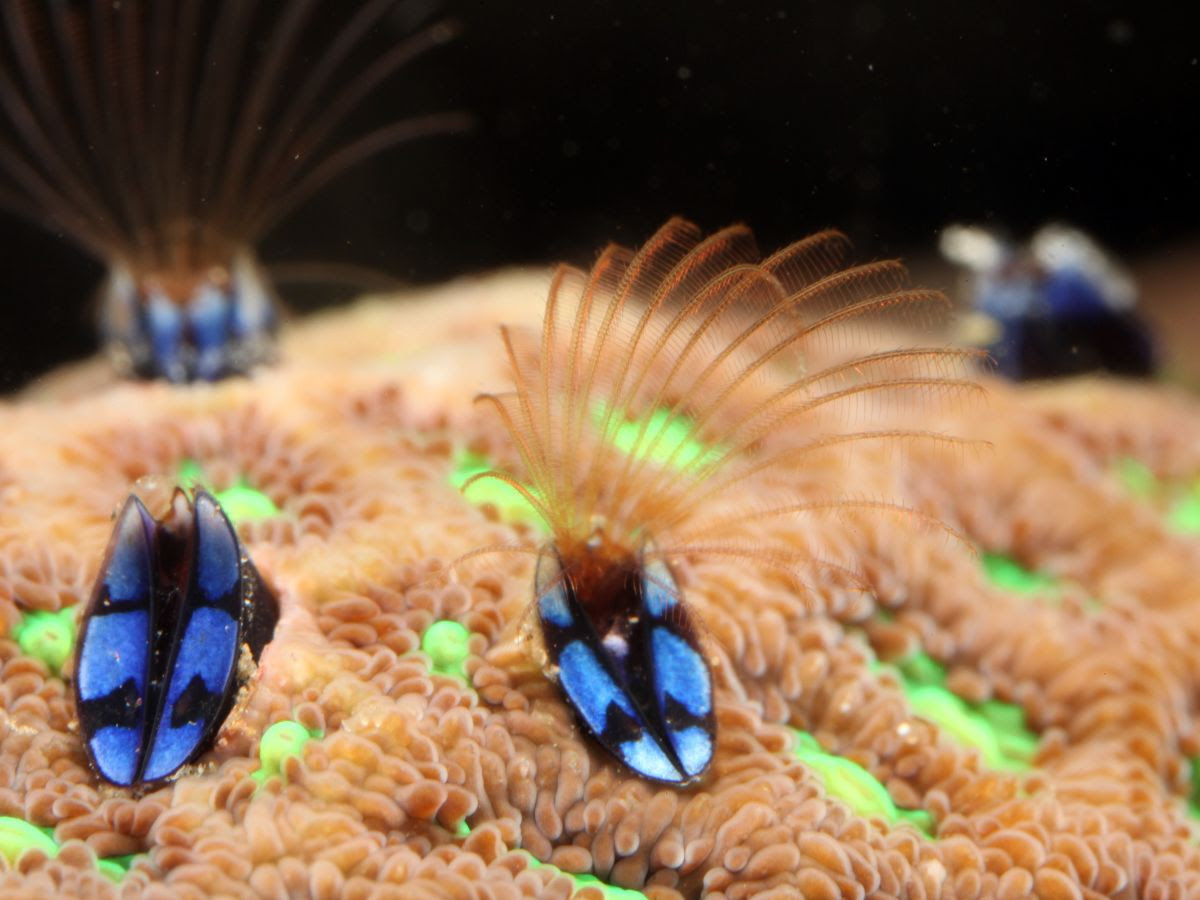

藤壺會大量附著在船底或礁石上,也會附著在海龜或鯨魚的身上,增加水下活動的負擔。然而,有些藤壺會發展出很特別的互利共生關係,「孔寬楯藤壺」是本期電子報主角,牠就可以安然的住在帶有劇毒的「火珊瑚」表面,要知道,火珊瑚的刺絲胞毒性,連潛水員碰到都會受傷,火珊瑚為何甘願接納這些不速之客呢?

中研院「研之有物」專訪了院內生物多樣性研究中心主任陳國勤特聘研究員,為我們揭開孔寬楯藤壺在火珊瑚表面的生存之道。秘密,就藏在藤壺獨特的生命週期裡。

藤壺幼體是關鍵:在劇毒中找到定居的家

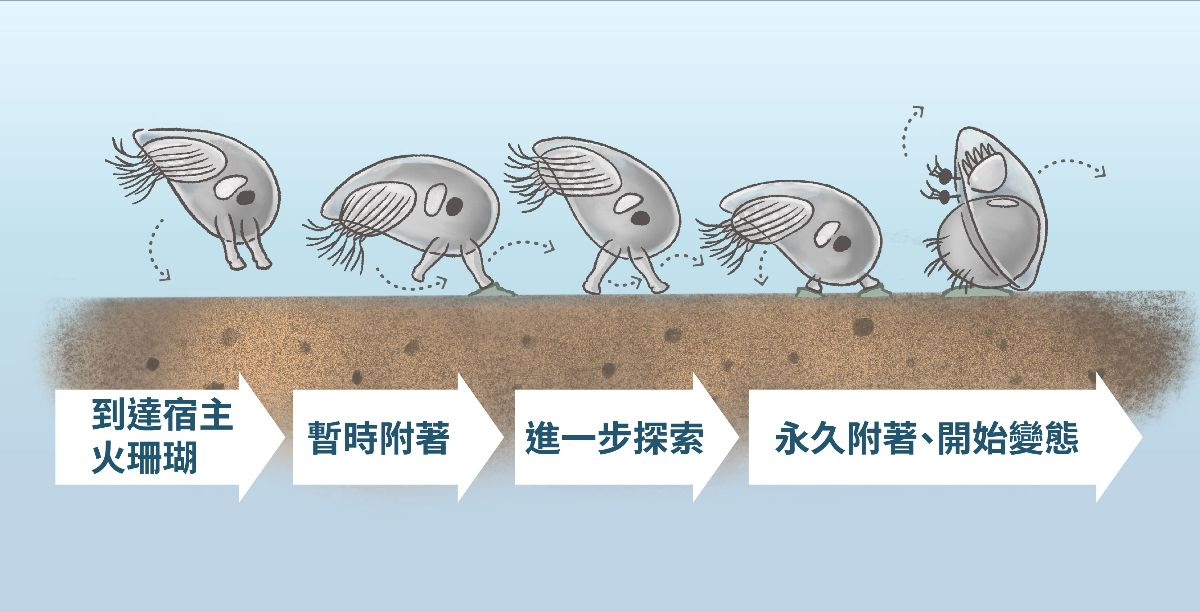

孔寬楯藤壺能在火珊瑚上定居,關鍵在於牠們的幼體。藤壺是會「變態」的生物,從可以自由游泳的「無節幼體」,歷經六個階段的成長,最後變態成比較沒那麼好動的「腺介幼體」,具有平滑外殼、六對泳肢和一對觸手 。

陳國勤團隊發現,孔寬楯藤壺的無節幼體游過火珊瑚時,還是會被刺絲胞攻擊並被吃掉。但神奇的是,到了腺介幼體階段,情況完全不同!當腺介幼體靠近時,火珊瑚的刺絲胞活動會大幅降低,即使幼體觸碰到也不會有事。腺介幼體就能順利在火珊瑚表面「散步」,尋找適合的定居點。

研究團隊推測,腺介幼體可能分泌了某些化學物質,抑制火珊瑚刺絲胞的活性 。這項研究也將朝生物化學方向深入探索。

「找房」三階段:謹慎的腺介幼體

腺介幼體在火珊瑚上定居,就像人類看房子一樣謹慎。陳國勤發現,牠們會經歷以下三個探索階段。廣範圍搜尋(wide searching):暫時附著,大步快速移動,尋找適合的區域。

近距離搜尋(close searching):放慢步調,小步移動,仔細檢查潛在的定居位置。

最後的檢查(inspection): 確定地點後,永久附著並開始變態為藤壺。第一階段,廣範圍探索的過程中,只要不滿意,腺介幼體會隨時游走。進入近距離的小步伐探索期,腺介幼體找到滿意的地方,會用觸手的附著盤固定自己,分泌膠黏蛋白,然後花將近一週的時間,慢慢變態成藤壺的模樣。

陳國勤說:「孔寬楯藤壺對火珊瑚情有獨鍾,只會在火珊瑚附著。」然而,生活在「火焰」上並不容易...

浴「火」生長的孔寬楯藤壺:50% 機率存活

陳國勤團隊觀察到,腺介幼體附著後,周圍的火珊瑚組織和蟲黃藻會先死亡退開。但隨著幼體變態成藤壺,火珊瑚組織和蟲黃藻會捲土重來,甚至生長覆蓋過藤壺的外殼,阻礙藤壺進食,此時藤壺死亡率 100% 。

另一種情況,也就是陳國勤實驗室觀察到的共生條件。年輕的孔寬楯藤壺會釋放化學物質,在外殼外圍形成一個圈狀結構,稱為「節疤環」,能減緩火珊瑚與蟲黃藻生長速度,避免自己被覆蓋過去。此時,藤壺有 50% 機率存活。成熟後的藤壺藏在火珊瑚裡,不僅能順利覓食,也更安全,不易被掠食者攻擊

陳國勤說。節疤環結構出現的原因,將會是接下來的研究重點。研究藤壺並不容易。陳國勤團隊花了 2 到 3 年,才完整記錄孔寬楯藤壺從幼體到附著變態的過程。

電子報篇幅有限,如果您想知道研究團隊如何飼養脆弱的藤壺幼體,或是想看看腺介幼體找房子的現場直播,歡迎點選閱讀本文~

閱讀本文

│延伸閱讀│

本期延伸閱讀主題是關於海洋生物。如果您想更廣泛地瞭解藤壺的故事,可以看看第一篇文章,陳國勤特聘研究員提供我們相當多精彩的照片,呈現藤壺的多樣性。不只火珊瑚,有些藤壺也會定居在珊瑚上,而四月底正是珊瑚的產卵季,為何珊瑚會同時間大量產卵?前任研究員野澤洋耕與林哲宏博士多年觀察發現,關鍵就在日落到月昇的黑暗時間。最後,不只藤壺有自己的生存之道,要在險惡的海洋環境活下去,曾庸哲副研究員發現,烏龜怪方蟹在代謝能力的演化,是適應極端化環境的關鍵。

無所不在的藤壺:與珊瑚共生的低調房客,也是操控螃蟹的蟹奴!

閱讀本文

珊瑚為何會同時間大量產卵?關鍵在日落到月昇的黑暗期!

閱讀本文

世間險惡!海洋生物透過「代謝能力」保小命