展覽評論

計算機老祖宗齊聚一堂

報道 2012年11月06日

Heidi Schumann for The New York Times

加州山景市計算機歷史博物館推出「革命:計算機的前2000年」展。

加州山景——一台1956年的IBM Ramac啟動盤和磁盤堆棧擺在面前,不是每個人都會立馬心跳加速的。同樣,對很多人來說,1959年的Telefunken RAT 700/2模擬計算機就像一台老掉牙的電話接線總機和德國潛艇儀錶盤的結合體。像我們這些上了點年紀、又在科技上有點悟性的人,回憶起精巧卓絕的計算尺(slide rule),嘴角還會泛起微笑。可如果是一台公文包大小卻幾乎拎不動的1981年產奧斯本計算機,那發光的5吋屏幕還能激起哪怕一丁點懷舊嗎?

包括這些在內的1000多件古老物品目前都放在計算機歷史博物館展出,博物館打出的旗號是“世界頭號致力於計算機革命及其影響的留存與呈現的博物館”。由於它講述的是這樣一種歷史,又在這樣一個地點,無論展品是多麼專業或者高深莫測,總是能吸引本不相干的人到這裡參觀。

博物館位於一個12萬平方英尺的巨大空間內,這裡原本是硅谷圖形公司(SGI)總部,就在貫穿硅谷的高速公路旁,離Google園區不遠。博物館在一定程度上是對本地產業的一種紀念,大概就跟英格蘭紐卡斯爾的煤礦博物館差 不多。它的捐助者有企業也有個人,一定程度上他們本身也是博物館的展覽內容。它展出的物品不只反映科技的歷史,也涉及商業。顯然它是希望吸引到廣泛的人群 的,但時不時又會透露出一種行家的視角,對樹木的興趣要超過森林。然而樹的種類是很豐富的,博物館的展品如此琳琅滿目,觀眾到了一定時候也會產生自己是行 家的感覺。

這家機構是1984年向公眾開放的,不過當時是在波士頓,環境跟現在截然不同,還要和兒童博物館共用一個空間。計算機博物館的收藏規模日益擴大,於 1999年遷往硅谷,目前使用的建築是在2002年購置的。不過機構真正自立門戶是在2011年,經過1900萬美元的改建工程後,它用一場名為“革命: 計算機的前2000年”的永久性展覽宣告2.5萬平方英尺的新空間開幕。

在原有的7.5萬件藏品基礎上,博物館收到了更多的文稿和物品捐贈,心氣也高了起來;它增添了一些流動性的小展覽、向業內先驅的致敬以及教育項目,作為對核心展覽的補充。

至於行家的那一面,最後往往成為一種優勢。這個課題的史詩維度,它的發展源頭和成敗的錯綜交織,不是行家怎麼可能看得清呢?計算機歷史記載着一些偉大的創意被迅速轉化成初始人工製品的過程。在行家眼裡,這種轉化的速度迅猛之極。

我們可以看到自20世紀中葉起的幾座歷史裡程碑:通用自動電子計算機(Univac)和電子數值積分計算機(Eniac),編程的觀念,數字存儲的 發展。我們還可以看到歷史留下的碎片被精心地保護了起來:真空管電路板,擠作一團的扭曲線纜,已經消失的公司的標誌,以及成排成排的機櫃。

這裡並非完美無瑕,但它講述的歷史令人神往,尤其是我們要知道,當今的發展進步已經和日常生活緊密結合到了一起,基本上無法察覺到。老一代的技術絕對不會這樣。

一開始幾個展廳的布置旨在讓我們意識到,自有記載以來,用於計算的機器在歷史上扮演着多麼重要的角色。算盤這個“可能是除手指以外最古老的持續使用 計算工具”,在這個展覽中很受重視。展覽安排了一段使用算盤的教學,另外我們還了解到,在1946年的日本,一名通曉新型電子計算器的美國陸軍士兵,和一 個將算盤用得出神入化的日本郵局職員比賽。五局裡算盤贏了四局。

展覽中最古老的計算機是一張“踏式計算器”的圖片,這種由萊布尼茨在17世紀末發明的四則計算器影響了後世近300年的計算器設計。門廳空間陳設着一台終極機械計算器:由查爾斯·巴貝奇(Charles Babbage)在150年前發明的“差分機”,至今仍可以使用。這台重5噸、長11英尺(約合335厘米——譯註),由8000個零件組成的機器可以進行複雜的數值表達式運算,並打印出結果。巴貝奇本人沒有把機器造出來,只是留下了圖紙;由倫敦科學博物館執行的製造工程花了將近二十年,直到2000年才完成(此處展出的是2008年委託製造的複製品)。

接下來,這段歷史之旅帶領我們從年代久遠的機械計算器向前走了一步,介紹了一項技術革新。這項革新對計算技術此後幾十年的發展起到了決定性作用,但用的卻是最普通的材料:一些打了孔的紙卡。這是赫爾曼·何樂禮(Herman Hollerith)的發明,此人在一個競賽中勝出,得到了為美國人口普查局作1890年人口普查數據分析的機會。他在6000多萬張卡片上根據每個人的個人特徵來打孔。然後根據孔的位置來整理數據。

這種做法聽起來技術含量夠低的,至於最初啟發了何樂禮的東西,比這還要低——19世紀初的賈卡提花機在印製布面圖案時會使用到一種帶孔卡片。往往是這些陳舊、簡單卻又有着驚人功用的想法,最終能成就技術的進步。

隨着年代發展,展覽中這種實用、基本的感覺漸漸減少了。這跟素材的問題有關。但有的時候,一項革新的重要性是需要做出更多闡釋的。模擬和數碼計算機的區別被解釋地太馬虎了。而相比硬件上的突破,編程領域的進步在展覽中體現的不充分,當然這方面呈現起來也確實不容易。

從各方面看,幾個效果最好的展品都是和歷史事件直接相關的。第二次世界大戰對科技潛能的發掘也許強於史上任何一場戰爭,尤其是密碼破譯和武器彈道計算這兩大需求,極大促進了計算技術的發展。這些研究改變了戰後計算技術的面貌。

博物館的歷史探尋還讓我們了解到電子計算機的發明權引發的專利之爭、數據存儲的演進、微處理器的開發,以及越來越複雜的計算機圖形技術。

我們看到了由西摩·克雷(Seymour Cray)設計、利用手工製作的超級計算機的一些組成部分(其中Cray–1是1976年到1982年之間全世界最快的電腦)。我們看到了電腦化的民用產 品,包括一台1969年的霍尼韋爾(Honeywell)迷你計算機,當時在內曼·馬庫斯(Neiman Marcus)商場被打上“廚房電腦”的標籤,售價10600美元。按照設想,這種電腦可以幫助那些富有的顧客處理連他們的廚師都應付不來的菜譜。(商品 圖冊上說:“要是她的廚藝能跟霍尼韋爾的計算本領一樣強該多好。”)另外,電子遊戲、移動計算、網絡和互聯網的發展,也在展覽中做了呈現。

隨着素材越來越接近我們的時代,展覽的論調開始變得不確定起來。重點在哪裡,為什麼這樣?後面的一些展廳已經有了過時的感覺,對某些東西(比如 “.com”的井噴式發展)說的太細,有些東西(取代PC的平板電腦和智能手機)又顯得不夠。過去15年的變化實在太大,司法部訴微軟的反壟斷官司,感覺 跟當年起訴IBM的那場一樣離奇(1982年該案因“證據不足”而撤訴)。

博物館如果能將視角進一步擴大,也許會有一些啟發:比如進一步探討科技發展與科幻小說的互動;計算機的大眾形象;圍繞着互聯網產生的烏托邦空想;或者政治文化中的變異。

不過,在某種程度上,這種展覽勢必要出現觀感的分歧——有人不滿,有人狂熱,不同的人會有截然不同的看法,並且會順時而變。這裡有如此多的內容,你 會忍不住順着一條線索往下走,希望它能帶你走得更遠;或者順着另一條線索,心裡想着可能是個死胡同。博物館在框架設計上還給創新和改變留出了許多空間。歸 根結底,它所探究的領域就是這樣,唯有往事才是真正靜態的。等它升級到2.0的時候,我會再來的。

包括這些在內的1000多件古老物品目前都放在計算機歷史博物館展出,博物館打出的旗號是“世界頭號致力於計算機革命及其影響的留存與呈現的博物館”。由於它講述的是這樣一種歷史,又在這樣一個地點,無論展品是多麼專業或者高深莫測,總是能吸引本不相干的人到這裡參觀。

博物館位於一個12萬平方英尺的巨大空間內,這裡原本是硅谷圖形公司(SGI)總部,就在貫穿硅谷的高速公路旁,離Google園區不遠。博物館在一定程度上是對本地產業的一種紀念,大概就跟英格蘭紐卡斯爾的煤礦博物館差 不多。它的捐助者有企業也有個人,一定程度上他們本身也是博物館的展覽內容。它展出的物品不只反映科技的歷史,也涉及商業。顯然它是希望吸引到廣泛的人群 的,但時不時又會透露出一種行家的視角,對樹木的興趣要超過森林。然而樹的種類是很豐富的,博物館的展品如此琳琅滿目,觀眾到了一定時候也會產生自己是行 家的感覺。

這家機構是1984年向公眾開放的,不過當時是在波士頓,環境跟現在截然不同,還要和兒童博物館共用一個空間。計算機博物館的收藏規模日益擴大,於 1999年遷往硅谷,目前使用的建築是在2002年購置的。不過機構真正自立門戶是在2011年,經過1900萬美元的改建工程後,它用一場名為“革命: 計算機的前2000年”的永久性展覽宣告2.5萬平方英尺的新空間開幕。

在原有的7.5萬件藏品基礎上,博物館收到了更多的文稿和物品捐贈,心氣也高了起來;它增添了一些流動性的小展覽、向業內先驅的致敬以及教育項目,作為對核心展覽的補充。

至於行家的那一面,最後往往成為一種優勢。這個課題的史詩維度,它的發展源頭和成敗的錯綜交織,不是行家怎麼可能看得清呢?計算機歷史記載着一些偉大的創意被迅速轉化成初始人工製品的過程。在行家眼裡,這種轉化的速度迅猛之極。

我們可以看到自20世紀中葉起的幾座歷史裡程碑:通用自動電子計算機(Univac)和電子數值積分計算機(Eniac),編程的觀念,數字存儲的 發展。我們還可以看到歷史留下的碎片被精心地保護了起來:真空管電路板,擠作一團的扭曲線纜,已經消失的公司的標誌,以及成排成排的機櫃。

這裡並非完美無瑕,但它講述的歷史令人神往,尤其是我們要知道,當今的發展進步已經和日常生活緊密結合到了一起,基本上無法察覺到。老一代的技術絕對不會這樣。

一開始幾個展廳的布置旨在讓我們意識到,自有記載以來,用於計算的機器在歷史上扮演着多麼重要的角色。算盤這個“可能是除手指以外最古老的持續使用 計算工具”,在這個展覽中很受重視。展覽安排了一段使用算盤的教學,另外我們還了解到,在1946年的日本,一名通曉新型電子計算器的美國陸軍士兵,和一 個將算盤用得出神入化的日本郵局職員比賽。五局裡算盤贏了四局。

展覽中最古老的計算機是一張“踏式計算器”的圖片,這種由萊布尼茨在17世紀末發明的四則計算器影響了後世近300年的計算器設計。門廳空間陳設着一台終極機械計算器:由查爾斯·巴貝奇(Charles Babbage)在150年前發明的“差分機”,至今仍可以使用。這台重5噸、長11英尺(約合335厘米——譯註),由8000個零件組成的機器可以進行複雜的數值表達式運算,並打印出結果。巴貝奇本人沒有把機器造出來,只是留下了圖紙;由倫敦科學博物館執行的製造工程花了將近二十年,直到2000年才完成(此處展出的是2008年委託製造的複製品)。

接下來,這段歷史之旅帶領我們從年代久遠的機械計算器向前走了一步,介紹了一項技術革新。這項革新對計算技術此後幾十年的發展起到了決定性作用,但用的卻是最普通的材料:一些打了孔的紙卡。這是赫爾曼·何樂禮(Herman Hollerith)的發明,此人在一個競賽中勝出,得到了為美國人口普查局作1890年人口普查數據分析的機會。他在6000多萬張卡片上根據每個人的個人特徵來打孔。然後根據孔的位置來整理數據。

這種做法聽起來技術含量夠低的,至於最初啟發了何樂禮的東西,比這還要低——19世紀初的賈卡提花機在印製布面圖案時會使用到一種帶孔卡片。往往是這些陳舊、簡單卻又有着驚人功用的想法,最終能成就技術的進步。

隨着年代發展,展覽中這種實用、基本的感覺漸漸減少了。這跟素材的問題有關。但有的時候,一項革新的重要性是需要做出更多闡釋的。模擬和數碼計算機的區別被解釋地太馬虎了。而相比硬件上的突破,編程領域的進步在展覽中體現的不充分,當然這方面呈現起來也確實不容易。

從各方面看,幾個效果最好的展品都是和歷史事件直接相關的。第二次世界大戰對科技潛能的發掘也許強於史上任何一場戰爭,尤其是密碼破譯和武器彈道計算這兩大需求,極大促進了計算技術的發展。這些研究改變了戰後計算技術的面貌。

博物館的歷史探尋還讓我們了解到電子計算機的發明權引發的專利之爭、數據存儲的演進、微處理器的開發,以及越來越複雜的計算機圖形技術。

我們看到了由西摩·克雷(Seymour Cray)設計、利用手工製作的超級計算機的一些組成部分(其中Cray–1是1976年到1982年之間全世界最快的電腦)。我們看到了電腦化的民用產 品,包括一台1969年的霍尼韋爾(Honeywell)迷你計算機,當時在內曼·馬庫斯(Neiman Marcus)商場被打上“廚房電腦”的標籤,售價10600美元。按照設想,這種電腦可以幫助那些富有的顧客處理連他們的廚師都應付不來的菜譜。(商品 圖冊上說:“要是她的廚藝能跟霍尼韋爾的計算本領一樣強該多好。”)另外,電子遊戲、移動計算、網絡和互聯網的發展,也在展覽中做了呈現。

隨着素材越來越接近我們的時代,展覽的論調開始變得不確定起來。重點在哪裡,為什麼這樣?後面的一些展廳已經有了過時的感覺,對某些東西(比如 “.com”的井噴式發展)說的太細,有些東西(取代PC的平板電腦和智能手機)又顯得不夠。過去15年的變化實在太大,司法部訴微軟的反壟斷官司,感覺 跟當年起訴IBM的那場一樣離奇(1982年該案因“證據不足”而撤訴)。

博物館如果能將視角進一步擴大,也許會有一些啟發:比如進一步探討科技發展與科幻小說的互動;計算機的大眾形象;圍繞着互聯網產生的烏托邦空想;或者政治文化中的變異。

不過,在某種程度上,這種展覽勢必要出現觀感的分歧——有人不滿,有人狂熱,不同的人會有截然不同的看法,並且會順時而變。這裡有如此多的內容,你 會忍不住順着一條線索往下走,希望它能帶你走得更遠;或者順着另一條線索,心裡想着可能是個死胡同。博物館在框架設計上還給創新和改變留出了許多空間。歸 根結底,它所探究的領域就是這樣,唯有往事才是真正靜態的。等它升級到2.0的時候,我會再來的。

The IBM PS/2: 25 Years of PC History

Here's a fond look back at the Personal System/2 series of PCs, which embarrassed IBM in the late 1980s but shaped the modern PC you know today.

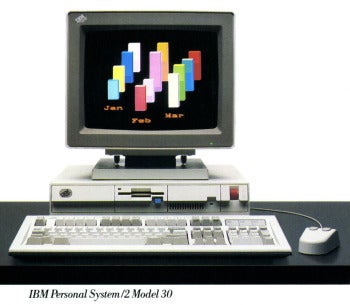

IBM PS/2 Model 30 adTwenty-five

years ago, IBM announced the Personal System/2 (PS/2), a new line of

IBM PC-compatible machines that capped an era of profound influence on

the personal computer market.

IBM PS/2 Model 30 adTwenty-five

years ago, IBM announced the Personal System/2 (PS/2), a new line of

IBM PC-compatible machines that capped an era of profound influence on

the personal computer market.By the time of the PS/2's launch in 1987, IBM PC clones--unauthorized work-alike machines that could utilize IBM PC hardware and software--had eaten away a sizable portion of IBM's own PC platform. Compare the numbers: In 1983, IBM controlled roughly 76 percent of the PC-compatible market, but in 1986 its share slipped to 26 percent.

IBM devised a plan to regain control of the PC-compatible market by introducing a new series of machines--the PS/2 line--with a proprietary expansion bus, operating system, and BIOS that would require clone makers to pay a hefty license if they wanted to play IBM's game. Unfortunately for IBM, PC clone manufacturers had already been playing their own game.

In the end, IBM failed to reclaim a market that was quickly slipping out of its grasp. But the PS/2 series left a lasting impression of technical influence on the PC industry that continues to this day.

Attack of the Clones

When IBM created the PC in 1981, it used a large number of easily obtainable, off-the-shelf components to construct the machine. Just about any company could have put them together into a computer system, but IBM added a couple of features that would give the machine a flavor unique to IBM. The first was its BIOS, the basic underlying code that governed use of the machine. The second was its disk operating system, which had been supplied by Microsoft.When Microsoft signed the deal to supply PC-DOS to IBM, it included a clause that allowed Microsoft to sell that same OS to other computer vendors--which Microsoft did (labeling it "MS-DOS") almost as soon as the PC launched.

Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.That

wasn't a serious problem at first, because those non-IBM machines,

although they ran MS-DOS, could not legally utilize the full suite of

available IBM PC software and hardware add-ons.

Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.That

wasn't a serious problem at first, because those non-IBM machines,

although they ran MS-DOS, could not legally utilize the full suite of

available IBM PC software and hardware add-ons.As the IBM PC grew in sales and influence, other computer manufacturers started to look into making PC-compatible machines. Before doing so, they had to reverse-engineer IBM's proprietary BIOS code using a clean-room technique to spare themselves from infringing upon IBM's copyright and trademarks.

First PC Clone: MPC 1600

In June 1982, Columbia Data Products did just that, and it introduced the first PC clone, the MPC 1600. Dynalogic and Compaq followed with PC work-alikes of their own in 1983, and soon, companies such as Phoenix Technologies developed IBM PC-compatible BIOS products that they freely licensed to any company that came calling. The floodgates had opened, and the PC-compatible market was no longer IBM's to own.At least in the early years, that market did not exist without IBM's influence. IBM's PC XT (1983) and PC AT (1984) both brought with them considerable innovations in PC design that cloners quickly copied.

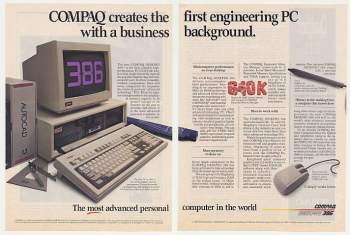

Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.comBut

that lead would not last forever. A profound shift in market leadership

occurred when Compaq released its DeskPro 386, a powerful 1986 PC

compatible that beat IBM to market in using Intel's 80386 CPU. It was an

embarrassing blow to IBM, and Big Blue knew that it had to do something

drastic to solidify its power.

Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.comBut

that lead would not last forever. A profound shift in market leadership

occurred when Compaq released its DeskPro 386, a powerful 1986 PC

compatible that beat IBM to market in using Intel's 80386 CPU. It was an

embarrassing blow to IBM, and Big Blue knew that it had to do something

drastic to solidify its power.[Related: The Computer Hardware Hall of Fame]

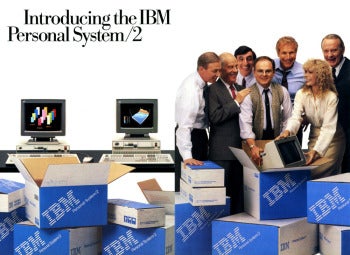

That something was the PS/2. The line launched in April 1987 with a high-powered ad campaign featuring the former cast of the hit MASH TV show, and a new slogan: "PS/2 It!"

Critics, who had seen more-powerful computers at lower prices, weren't particularly impressed, and everyone immediately knew that IBM planned to use the PS/2 to pull the rug out from beneath the PC-compatible industry. But the new PS/2 did have some tricks up its sleeve that would keep cloners busy for another couple of years in an attempt to catch up.

Four Initial Models

IBM announced four PS/2 models during its April 1987 launch: the Model 30, 50, 60, and 80. They ranged dramatically in power and price; on the low end, the Model 30 (roughly equivalent to a PC XT) contained an 8MHz 8086 CPU, 640KB of RAM, and a 20MB hard drive, and retailed for $2295 (about $4642 in 2012 dollars when adjusted for inflation).The most powerful configuration of the Model 80 came equipped with a 20MHz 386 CPU, 2MB of RAM, and a 115MB hard drive for a total cost of $10,995 (about $22,243 today). Neither configuration included an OS--you had to buy PC-DOS 3.3 for an extra $120 ($242 today).

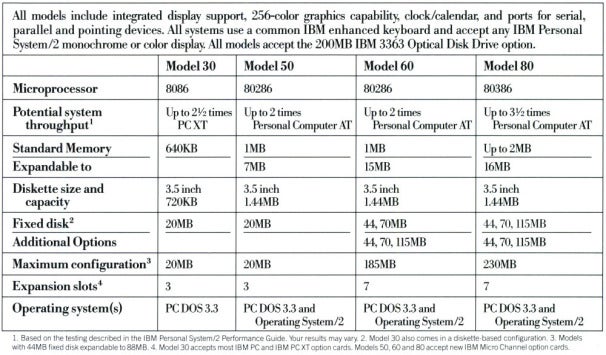

The following chart from IBM offers a more detailed view of the systems available during the 1987 launch, and illustrates just how complex the variety could be.

IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987.

IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987.Every unit in the line included at least one feature new to IBM's PC offerings--and the market in general. In the following sections, I'll discuss those new features and how they affected the PC industry.

Integrated I/O Functionality, New Memory Standard

From the IBM PC in 1981 through the PC AT in 1984, IBM preferred to keep a minimum of features in the base unit. Instead, it allowed users to extend their systems with expansion cards that plugged into the internal slots. This meant that a 1981 PC, which shipped with five slots, left little room for expansion when it already contained a graphics card, a disk controller, a serial card, and a printer card--a common configuration at the time.With the PS/2, IBM chose to integrate many of those commonly used I/O boards into the motherboard itself. Each model in the PS/2 line included a built-in serial port, parallel port, mouse port, video adapter, and floppy controller, which freed up internal slots for other uses.

Computers in the PS/2 series also had a few other built-in advancements, such as the 16550 UART, a chip that allowed faster serial communications (useful when using a modem), as well as 72-pin RAM SIMM (single in-line memory module) sockets. Both items became standard across the industry over time.

PS/2 Keyboard and Mouse Ports

An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.The

built-in mouse port I mentioned earlier is worth noting in more detail.

Each machine in the PS/2 line included a redesigned keyboard port and a

new mouse port, both of which used 6-pin mini-DIN connectors.

An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.The

built-in mouse port I mentioned earlier is worth noting in more detail.

Each machine in the PS/2 line included a redesigned keyboard port and a

new mouse port, both of which used 6-pin mini-DIN connectors.IBM intended the mouse, as a peripheral, to play a major part in the PS/2 system. The company promised a new graphical OS (which I'll talk about later) that would compete with the Macintosh in windowing functionality.

Even today, many new PCs ship with "PS/2 connectors" for mice and keyboards, although they have been steadily falling out of fashion in favor of USB ports.

New Floppy Drives

Every model in the PS/2 line contained a 3.5-inch microfloppy drive, a Sony-developed technology that, until then, had been featured most prominently in Apple Macintosh computers.The low-end PS/2 Model 30 shipped with a drive that could read and write 720KB double-density disks. Other models introduced something completely new: a 1440KB high-density floppy drive that would become the PC floppy drive standard for the next 20 years.

IBM's use of the 3.5-inch floppy drive was new in the PC-compatible world. Up to that point, IBM itself had favored traditional 5.25-inch disk drives. This drastic format shift initially came as a great annoyance to PC users with large libraries of software on 5.25-inch disks.

Although IBM did offer an external 5.25-inch drive option for the PS/2 line, cloners quickly followed suit with their own 3.5-inch drives, and many commercial software applications began shipping with both 5.25-inch and 3.5-inch floppies in the box.

VGA and MCGA

In many ways, the PS/2 line is most notable, historically, for its introduction of the Video Graphics Array standard.Among its many modes, VGA could display 640-by-480-pixel resolution with 16 colors on screen, and a resolution of 320 by 200 pixels with 256 colors, which was a significant improvement for PC-compatible systems at the time. It was also fully backward-compatible with the earlier Enhanced Graphics Adapter and Color Graphics Adapter standards from IBM.

In addition, the PS/2 line introduced what we now colloquially call a "VGA connector"--a 20-pin D-type socket that also became an industry standard.

The low-end Model 30 shipped with an integrated MCGA graphics adapter that could display a resolution of 320 by 200 pixels with 256 colors as well, but could display only 640 by 480 pixels in monochrome and was not backward-compatible with EGA. MCGA met its end after IBM included it in only a few low-end versions of the PS/2; cloners never favored it.

Micro Channel Architecture

The crowning glory of the PS/2 line's hardware improvements was supposed to be its new expansion bus, dubbed Micro Channel Architecture. Every initial PS/2 model except the low-end Model 30 shipped with internal MCA slots for use with expansion cards.The Model 30 included three ISA expansion slots--the type used in the original IBM PC and extended for the PC AT line. Not surprisingly, the rest of the PC-compatible industry utilized the ISA expansion bus as well, so any PC-compatible machine could use almost all the cards created for other PC compatibles.

MCA NIC IBM 83X9648 16-bit-card. Image: Courtesy of Appaloosa, Wikimedia CommonsWith

the PS/2, IBM saw the opportunity to create an entirely new and

improved expansion bus whose design it would strictly control and

license, thus limiting the industry's ability to clone the PS/2 machines

without paying a toll to IBM.

MCA NIC IBM 83X9648 16-bit-card. Image: Courtesy of Appaloosa, Wikimedia CommonsWith

the PS/2, IBM saw the opportunity to create an entirely new and

improved expansion bus whose design it would strictly control and

license, thus limiting the industry's ability to clone the PS/2 machines

without paying a toll to IBM.ISA had become slow and limiting by mid-1980s standards. MCA improved on it by increasing the data width from 16 bits to either 16 bits or 32 bits (which allowed more data to transmit over the bus at a time) and by improving the bus speed from 8MHz to 10MHz.

MCA also introduced a limited form of plug-and-play functionality, wherein each expansion card carried with it a unique 16-bit ID number that a PS/2 machine could identify to help it automatically configure the card.

In theory, that method sounded much easier than the jumper-setting necessary on earlier ISA cards; but in practice, it turned a bit unwieldy. Older IBM Reference Disks (the utilities that set the system's basic CMOS settings) would not know the IDs for newer cards, which required IBM to release frequent Reference Disk updates. So unless you always had the latest version (which was impossible in the pre-Internet-update era), you probably needed a specially designed disk to use your new MCA expansion card.

The PC clone industry did not take kindly to the power play represented by IBM's new MCA bus. Just one year after its introduction, a consortium of nine PC clone manufacturers introduced its own rival standard, EISA, which extended the earlier ISA bus to 32 bits with minimal licensing cost. Ultimately, few desktop PCs utilized EISA. The standard remained 16-bit ISA slots until Intel's introduction of PCI, yet another new bus standard, in the early 1990s.

OS/2

MCA did not help the PS/2's fortunes, but another major factor worked to sink the PS/2 as a successful platform. The high-end Model 80 PS/2As

previously mentioned, IBM planned to release the PS/2 with a completely

new, proprietary operating system called OS/2, which would take

advantage of new features of the 386 CPU in the high-end Model 80,

utilize the built-in mouse port, and also provide a graphical windowing

environment comparable to that of the Apple Macintosh.

The high-end Model 80 PS/2As

previously mentioned, IBM planned to release the PS/2 with a completely

new, proprietary operating system called OS/2, which would take

advantage of new features of the 386 CPU in the high-end Model 80,

utilize the built-in mouse port, and also provide a graphical windowing

environment comparable to that of the Apple Macintosh.There was only one problem: IBM hired Microsoft, creator of PC-DOS (and MS-DOS and Windows), to make it.

At the time, Microsoft was enjoying a boom in business from all the MS-DOS licenses it was selling to PC clone vendors, and a proprietary PC OS was most definitely not in its best interest.

So, when IBM announced that the full version of OS/2 would be delayed until late 1988 (with a simple DOS-like preview version coming in late 1987), more than a few conspiracy theories flew around the industry.

Meanwhile, Microsoft was prepping a launch of Windows 2.0, which would have most of the features of OS/2, in late 1987--over a year before IBM would launch OS/2. The situation was a painful lesson in letting your competitor create products for you. Amazingly, IBM did not recognize (and act against) that potential conflict of interest.

The End of IBM's PC Dominance

After launch, the IBM PS/2 line sold well for a short time (about 1.5 million units sold by January 1988), but its comparatively high cost versus PC-compatible brands steered most consumer-level users away from the systems.Even worse for IBM, just about every advance it made in the PS/2 ended up being matched (or cloned) and then surpassed by the clone vendors. Sales of the PS/2 slipped dramatically through the rest of the 1980s, and the PS/2 line became an embarrassing public disaster for IBM.

By 1990, it was abundantly clear that IBM no longer guided the PC-compatible market. And in 1994, Compaq replaced IBM as the number one PC vendor in the United States.

IBM stuck with the PC market until 2004, when it sold its PC division to Lenovo. By that time IBM had scored a few more consumer PC innovations with graphics standards and portable computers (especially with the ThinkPad line), but none of its machines after the PS/2 would have the same impact as those it released in the early and mid-1980s.

沒有留言:

張貼留言