As the Periodic Table of the Elements turns 150-years-old, Princeton Professor of History Michael D. Gordin reflects on its story and why its creator, Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev, is so compelling.

Science historian Gordin discusses Mendeleev’s periodic table, now turning 150 years old

Feb. 1, 2019 1:41 p.m.

Michael Gordin

A century and a half ago, a Russian chemistry professor published a classification of all the known elements, organized by atomic weight. Today, the system that he created for his students — plus some updates and including about twice as many elements — is found in chemistry classrooms around the world.

Now known as the Periodic Table of the Elements, it was first shaped in February 1869 by Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834–1907), then a professor of general chemistry at St. Petersburg University, in the capital of the Russian Empire. The story of the “attempt at a system of elements,” as Mendeleev titled his initial publication, has been laid out clearly by science historian Michael Gordin in a special issue of the journal Science.

Gordin, Princeton’s Rosengarten Professor of Modern and Contemporary History, has said he was drawn to the history of science because of what it can teach scientists and nonscientists alike. He is also the director of the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts and the author of several books, including a 2004 biography of Mendeleev; a second edition was published in December by Princeton University Press.

A revised edition of Gordin’s 2004 biography of Dmitrii Mendeleev was published by Princeton University Press in December 2018.

Why do you think Mendeleev’s arrangement has held up over time, while the prior attempts have largely been forgotten?

There are two primary reasons for this. The first is that Mendeleev did something rather surprising that none of the five other preceding tabular arrangements of elements did: he left empty spaces in the table when he thought that elements were better placed elsewhere — that is, he did not assume that chemistry had found all the elements yet — and then predicted the chemical and physical properties in detail for three of them. Those were discovered over the next two decades as gallium, scandium and germanium. Before Mendeleev, this kind of elemental prediction simply hadn’t been tried before, let alone been successful. The successful discoveries, which Mendeleev rooted in his periodic system, made people take notice of what he had done in a way that was not matched by the others.

The second reason tells you a little about Mendeleev’s personality. When a dispute over who deserved full credit for the table — Mendeleev alone or him in combination with Julius Lothar Meyer, who had also developed an impressive system at roughly the same time — Mendeleev was very aggressive in defending his priority and his right to sole credit for the system. Although at first the chemical community was inclined to give them both credit, over time the accolades went to Mendeleev alone. The fact that he died after all of his competitors meant that he had a role to play in shaping the story.

What is the biggest shift between his version and the one in every chemistry classroom? What, if anything, has remained unchanged?

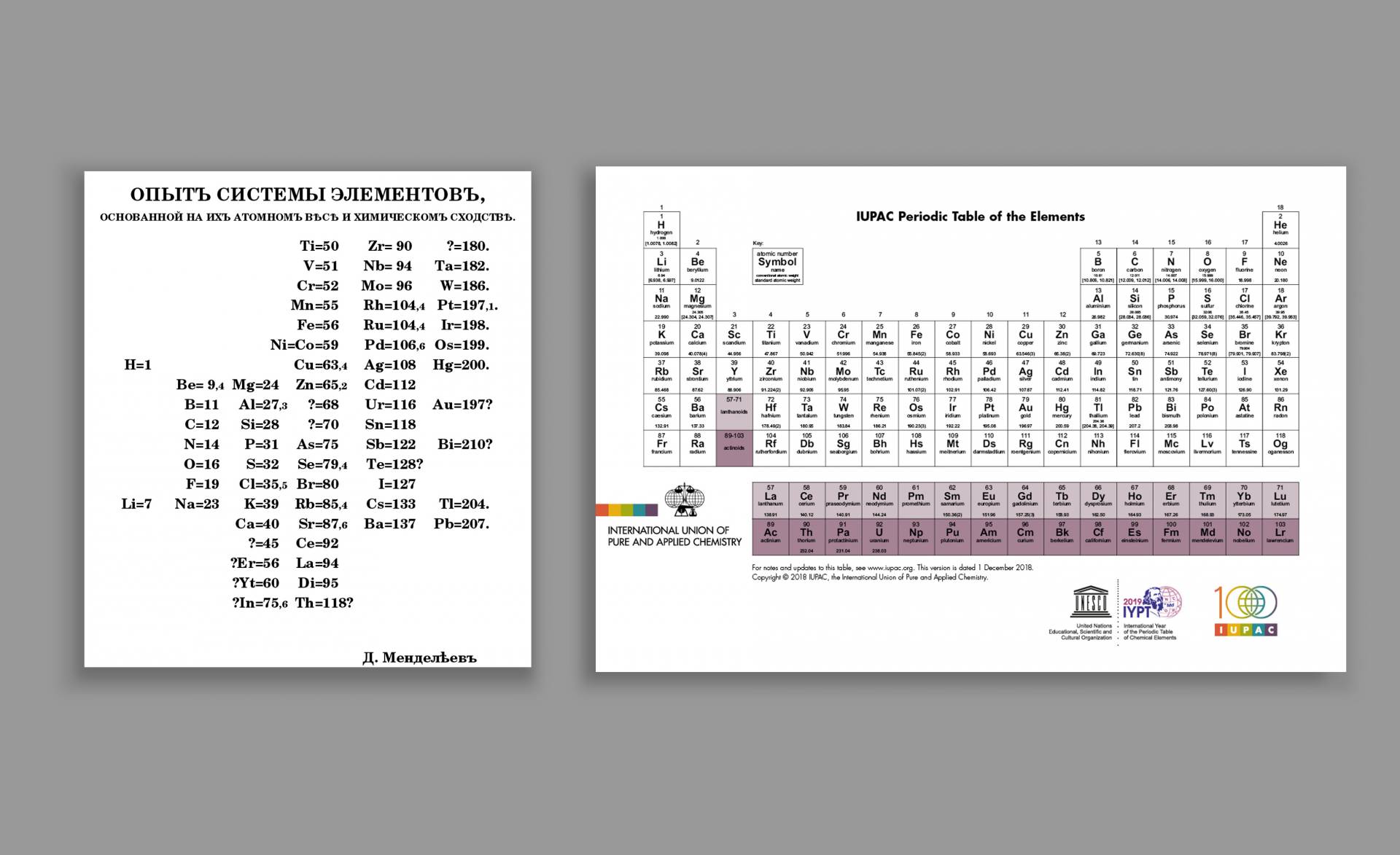

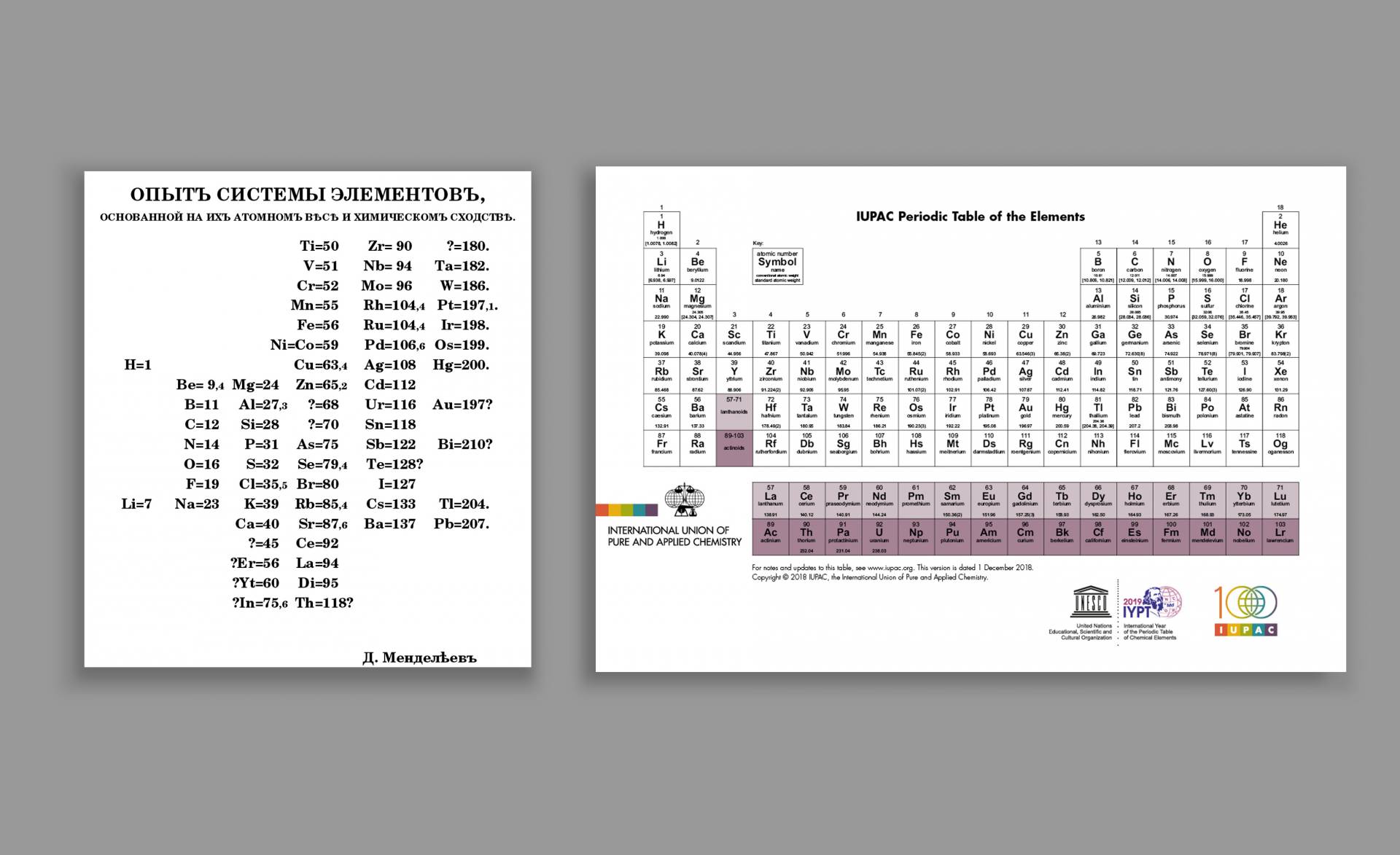

The biggest shift is that the table is currently arranged using the atomic number, the number of protons in the nucleus of a chemical atom. The number of positively charged protons determines the number of orbiting electrons, and those electrons are responsible for the element’s chemical properties. Mendeleev did not know about protons. (The electron itself, discovered in 1897, was something Mendeleev remained suspicious of until his death in 1907.) Mendeleev, by contrast, organized the elements by increasing atomic weight. This is a reasonably good proxy for what we now understand to be really going on, but it isn’t infallible. Certain elements, such as tellurium and iodine, are arranged with the heavier element (tellurium) first in both Mendeleev’s order and on today’s table. Mendeleev thought this was a frustrating anomaly; for us, it is not a problem at all, since we don’t think atomic weight is the determining factor.

What has stayed the same is perhaps more remarkable: Mendeleev got the families of chemical elements (that is, the vertical columns) right. Chemists have added a lot of elements to the bottom of the table and a whole new family of noble gases on the right end, but they haven’t rearranged the elements in the middle. Of the 63 elements known when Mendeleev put his first table together, he got the order correct.

You have spent years studying Mendeleev. What makes him such a compelling figure to you?

I have been fascinated by both Russian history and the history of science for a long time. There are many places where those two interests overlap, but probably the most widely known name of a Russian scientist is Mendeleev. (Ivan Pavlov is another good candidate.) As someone interested in chemistry, I was encouraged in graduate school to pursue a dissertation providing a biographical study of Mendeleev. I found him a fascinating figure in many ways. In his former apartment on the grounds of St. Petersburg University you can find a museum to his life and also an astonishingly vast archive of his correspondence, research notes and library. The more I dug, the more I found out.

Left: Mendeleev titled his February 1869 publication “An Attempt at a System of Elements, Based on Their Atomic Weight and Chemical Affinity.” Mendeleev’s table was designed to be read top to bottom and then left to right. To orient it like the modern table, it needs to be rotated 90 degrees clockwise and then flipped across its vertical axis. Right: The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) regularly updates its familiar “Periodic Table of the Elements.” The most recent iteration, published Dec. 1, 2018, includes a newly revised atomic weight range for argon.

What would you like people to know about Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev?

There’s a lot more to him than just the periodic system of chemical elements! He lived for a long time — 1834 to 1907 — which meant that he was 35 when he published his first table. Although he worked on the table for the next three years and then returned to the topic on and off again for the rest of his life, he spent most of his career doing many other things: he was a primary adviser to the Ministry of Finances and organized a highly protectionist tariff for Russia; he was the key mover in the introduction of the metric system to Imperial Russia; he led a public campaign to debunk séances of spiritualists; he developed a form of smokeless gunpowder; and he was a highly visible and influential member of St. Petersburg culture during one of its most dynamic periods. There is a quite vibrant personality behind that table on the classroom wall.

“Ordering the elements: Elegant and intuitive, today’s periodic table belies the hard-won discoveries hidden within,” by Michael Gordin, appears in the Feb. 1, 2019 issue of Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.aav7350). The Periodic Table of the Elements, copyright © 2018 International Union of Pure Applied Chemistry, is reproduced with permission.

科學歷史學家Gordin討論了門捷列夫的周期表,現在已經有150年的歷史了

2019年2月1日下午1:41

邁克爾格丁

一個半世紀以前,一位俄羅斯化學教授發表了一份按原子量組織的所有已知元素的分類。今天,他為學生創建的系統 - 加上一些更新,包括大約兩倍的元素 - 可以在世界各地的化學課堂中找到。

現在被稱為元素週期表,它首先於1869年2月由Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev(1834-1907)塑造,後者是俄羅斯帝國首都聖彼得堡大學的普通化學教授。正如門捷列夫所做的那樣,“試圖建立元素系統”的故事由科學歷史學家邁克爾·格丁(Michael Gordin)在“科學”雜誌的特刊中清楚地闡述。

Gordin,現代普林斯頓的教授玫瑰園和當代史,說他被吸引到科學史,因為它可以教科學家和非科學家的一致好評。他還是文科研究員協會的主任,也是幾本書的作者,包括2004年的門捷列夫傳記; 普林斯頓大學出版社於12月出版了第二版。

普林斯頓大學出版社於2018年12月出版了Gordin 2004年Dmitrii Mendeleev傳記的修訂版。

為什麼你認為門捷列夫的安排隨著時間的推移而持續,而之前的嘗試基本上已被遺忘?

這有兩個主要原因。首先,門捷列夫做了一件相當令人驚訝的事情,其他五個元素的表格排列都沒有做到:當他認為元素更好地放在其他地方時,他在表格中留下了空位 - 也就是說,他沒有假設化學已經發現所有元素 - 然後預測其中三個的詳細化學和物理特性。這些在未來二十年被發現為鎵,鈧和鍺。在門捷列夫之前,這種元素預測之前根本沒有嘗試過,更不用說成功了。門捷列夫根據他的周期系統取得的成功發現使人們注意到他所做的事情與其他人無法匹敵。

第二個原因告訴你一點關於門捷列夫的個性。當一個人應該獲得全額信用的爭議 - 單獨的門捷列夫或者他與朱利葉斯洛薩梅耶一起,他們在大致相同的時間也建立了一個令人印象深刻的系統 - 門捷列夫非常咄咄逼人地捍衛他的優先權和他的獨家信用權對於系統。雖然起初化學界傾向於給予他們信任,但隨著時間的推移,這一榮譽僅僅歸功於門捷列夫。他在所有競爭對手之後去世的事實意味著他在塑造故事方面可以發揮作用。

他的版本與每個化學教室的版本之間的最大轉變是什麼?什麼,如果有的話,保持不變?

最大的轉變是該表目前使用原子序數排列,即化學原子核中的質子數。帶正電的質子的數量決定了軌道電子的數量,而那些電子是元素化學性質的原因。門捷列夫不了解質子。(電子本身,發現於1897年,是門捷列夫在1907年去世前一直懷疑的。)相比之下,門捷列夫通過增加原子量來組織這些元素。對於我們現在理解的實際情況來說,這是一個相當不錯的代理,但它並非絕對可靠。某些元素,如碲和碘,在Mendeleev的順序和今天的表格中首先與較重的元素(碲)排列。門捷列夫認為這是令人沮喪的異常現象; 為了我們,

保持不變的可能更為顯著:門捷列夫得到了化學元素(即垂直列)的系列。化學家在桌子底部添加了許多元素,在右端添加了一整套新的惰性氣體,但他們沒有在中間重新排列元素。在門捷列夫把他的第一張桌子放在一起的63個元素中,他得到了正確的命令。

你花了數年時間研究門捷列夫。是什麼讓他成為如此引人注目的人物?

長期以來,我對俄羅斯歷史和科學史都著迷。在這兩個利益重疊的地方有很多,但俄羅斯科學家最著名的名字可能是門捷列夫。(Ivan Pavlov是另一個很好的候選人。)作為對化學感興趣的人,我在研究生院受到鼓勵,繼續學習提供門捷列夫的傳記研究。我在很多方面發現他是一個迷人的人物。在聖彼得堡大學的前公寓裡,你可以找到他生活中的博物館,還有他的通信,研究筆記和圖書館的驚人檔案。我挖的越多,我發現的就越多。

左:門捷列夫題為他1869年2月的出版物“基於原子量和化學親和力的元素系統的嘗試。”門捷列夫的表被設計為從上到下,然後從左到右。要像現代桌子一樣定位它,它需要順時針旋轉90度,然後翻過它的垂直軸。右圖:國際純粹與應用化學聯合會(IUPAC)定期更新其熟悉的“元素週期表”。最新的迭代,發佈於2018年12月1日,包括新修訂的氬原子量範圍。

您想了解更多關於Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev的消息?

除了周期性的化學元素系統,他還有很多東西!他活了很長時間 - - 1834年到1907年 - 這意味著他出版第一張桌子時已經35歲了。雖然他在接下來的三年裡一直在桌上工作,然後在他的餘生中一次又一次地回到這個話題,但他的大部分職業生涯都做了很多其他事情:他是財政部的主要顧問,為俄羅斯組織了高度保護主義的關稅; 他是向帝國俄羅斯引入公制系統的關鍵推動者; 他領導了一場揭露靈性主義者的公開運動; 他開發了一種無菸火藥; 在一個最具活力的時期,他是聖彼得堡文化中一位極具影響力和影響力的成員。教室牆上的桌子背後有一種非常有活力的個性。

“ 訂購元素:優雅和直觀,今天的周期表掩蓋了隱藏在其中的來之不易的發現,”Michael Gordin出現在2019年2月1日的“科學”雜誌(DOI:10.1126 / science.aav7350)中。元素週期表,版權所有©2018國際純應用化學聯合會,經許可複制。

沒有留言:

張貼留言