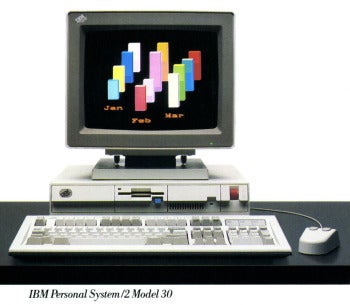

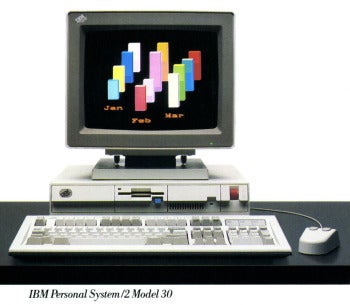

IBM PS/2 Model 30 ad

IBM PS/2 Model 30 adTwenty-five

years ago, IBM announced the Personal System/2 (PS/2), a new line of

IBM PC-compatible machines that capped an era of profound influence on

the personal computer market.

By the time of the PS/2's launch in 1987, IBM PC clones--unauthorized

work-alike machines that could utilize IBM PC hardware and

software--had eaten away a sizable portion of IBM's own PC platform.

Compare the numbers: In 1983, IBM controlled roughly 76 percent of the

PC-compatible market, but in 1986 its share slipped to 26 percent.

IBM devised a plan to regain control of the PC-compatible market by

introducing a new series of machines--the PS/2 line--with a proprietary

expansion bus, operating system, and BIOS that would require clone

makers to pay a hefty license if they wanted to play IBM's game.

Unfortunately for IBM, PC clone manufacturers had already been playing

their own game.

In the end, IBM failed to reclaim a market that was quickly slipping

out of its grasp. But the PS/2 series left a lasting impression of

technical influence on the PC industry that continues to this day.

Attack of the Clones

When IBM created the PC in 1981, it used a large number of easily

obtainable, off-the-shelf components to construct the machine. Just

about any company could have put them together into a computer system,

but IBM added a couple of features that would give the machine a flavor

unique to IBM. The first was its

BIOS,

the basic underlying code that governed use of the machine. The second

was its disk operating system, which had been supplied by Microsoft.

When Microsoft signed the deal to supply PC-DOS to IBM, it included a

clause that allowed Microsoft to sell that same OS to other computer

vendors--which Microsoft did (labeling it "MS-DOS") almost as soon as

the PC launched.

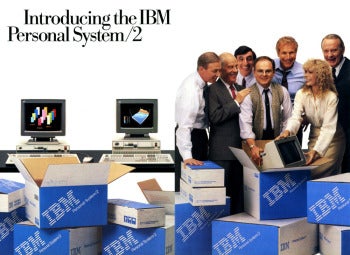

Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.

Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.That

wasn't a serious problem at first, because those non-IBM machines,

although they ran MS-DOS, could not legally utilize the full suite of

available IBM PC software and hardware add-ons.

As the IBM PC grew in sales and influence, other computer

manufacturers started to look into making PC-compatible machines. Before

doing so, they had to reverse-engineer IBM's proprietary BIOS code

using a

clean-room technique to spare themselves from infringing upon IBM's copyright and trademarks.

First PC Clone: MPC 1600

In June 1982, Columbia Data Products did just that, and it introduced

the first PC clone, the MPC 1600. Dynalogic and Compaq followed with PC

work-alikes of their own in 1983, and soon, companies such as Phoenix

Technologies developed IBM PC-compatible BIOS products that they freely

licensed to any company that came calling. The floodgates had opened,

and the PC-compatible market was no longer IBM's to own.

At least in the early years, that market did not exist without IBM's

influence. IBM's PC XT (1983) and PC AT (1984) both brought with them

considerable innovations in PC design that cloners quickly copied.

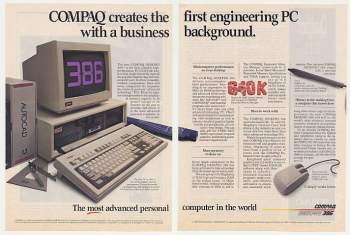

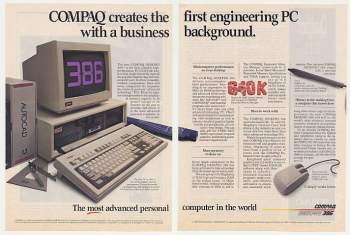

Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.com

Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.comBut

that lead would not last forever. A profound shift in market leadership

occurred when Compaq released its DeskPro 386, a powerful 1986 PC

compatible that beat IBM to market in using Intel's 80386 CPU. It was an

embarrassing blow to IBM, and Big Blue knew that it had to do something

drastic to solidify its power.

[Related:

The Computer Hardware Hall of Fame]

That something was the PS/2. The line launched in April 1987 with a

high-powered ad campaign featuring the former cast of the hit

MASH TV show, and a new slogan: "PS/2 It!"

Critics, who had seen more-powerful computers at lower prices,

weren't particularly impressed, and everyone immediately knew that IBM

planned to use the PS/2 to pull the rug out from beneath the

PC-compatible industry. But the new PS/2 did have some tricks up its

sleeve that would keep cloners busy for another couple of years in an

attempt to catch up.

Four Initial Models

IBM announced four PS/2 models during its April 1987 launch: the

Model 30, 50, 60, and 80. They ranged dramatically in power and price;

on the low end, the Model 30 (roughly equivalent to a PC XT) contained

an 8MHz 8086 CPU, 640KB of RAM, and a 20MB hard drive, and retailed for

$2295 (about $4642 in 2012 dollars when adjusted for inflation).

The most powerful configuration of the Model 80 came equipped with a

20MHz 386 CPU, 2MB of RAM, and a 115MB hard drive for a total cost of

$10,995 (about $22,243 today). Neither configuration included an OS--you

had to buy PC-DOS 3.3 for an extra $120 ($242 today).

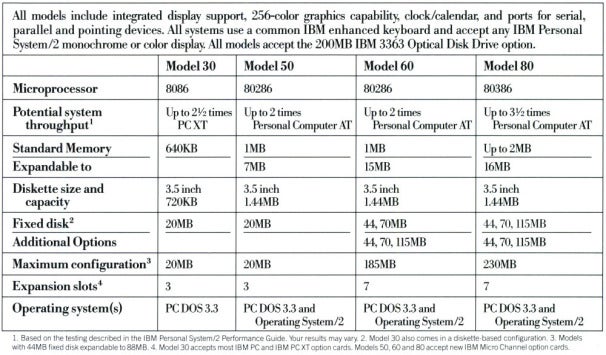

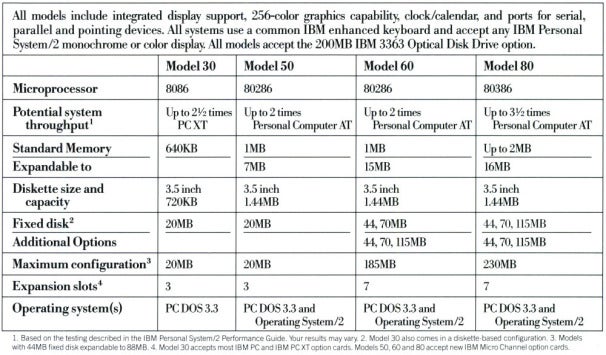

The following chart from IBM offers a more detailed view of the

systems available during the 1987 launch, and illustrates just how

complex the variety could be.

IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987.

IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987.

Every unit in the line included at least one feature new to IBM's PC

offerings--and the market in general. In the following sections, I'll

discuss those new features and how they affected the PC industry.

Integrated I/O Functionality, New Memory Standard

From the IBM PC in 1981 through the PC AT in 1984, IBM preferred to

keep a minimum of features in the base unit. Instead, it allowed users

to extend their systems with expansion cards that plugged into the

internal slots. This meant that a 1981 PC, which shipped with five

slots, left little room for expansion when it already contained a

graphics card, a disk controller, a serial card, and a printer card--a

common configuration at the time.

With the PS/2, IBM chose to integrate many of those commonly used I/O

boards into the motherboard itself. Each model in the PS/2 line

included a built-in serial port, parallel port, mouse port, video

adapter, and floppy controller, which freed up internal slots for other

uses.

Computers in the PS/2 series also had a few other built-in advancements, such as the

16550 UART, a chip that allowed faster serial communications (useful when using a modem), as well as

72-pin RAM SIMM (single in-line memory module) sockets. Both items became standard across the industry over time.

PS/2 Keyboard and Mouse Ports

An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.

An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.The

built-in mouse port I mentioned earlier is worth noting in more detail.

Each machine in the PS/2 line included a redesigned keyboard port and a

new mouse port, both of which used 6-pin mini-DIN connectors.

IBM intended the mouse, as a peripheral, to play a major part in the

PS/2 system. The company promised a new graphical OS (which I'll talk

about later) that would compete with the Macintosh in windowing

functionality.

Even today, many new PCs ship with "PS/2 connectors" for mice and

keyboards, although they have been steadily falling out of fashion in

favor of USB ports.

New Floppy Drives

Every model in the PS/2 line contained a 3.5-inch microfloppy drive, a

Sony-developed technology that, until then, had been featured most

prominently in Apple Macintosh computers.

The low-end PS/2 Model 30 shipped with a drive that could read and

write 720KB double-density disks. Other models introduced something

completely new: a 1440KB high-density floppy drive that would become the

PC floppy drive standard for the next 20 years.

IBM's use of the 3.5-inch floppy drive was new in the PC-compatible

world. Up to that point, IBM itself had favored traditional 5.25-inch

disk drives. This drastic format shift initially came as a great

annoyance to PC users with large libraries of software on 5.25-inch

disks.

Although IBM did offer an external 5.25-inch drive option for the

PS/2 line, cloners quickly followed suit with their own 3.5-inch drives,

and many commercial software applications began shipping with both

5.25-inch and 3.5-inch floppies in the box.

IBM PS/2 Model 30 adTwenty-five

years ago, IBM announced the Personal System/2 (PS/2), a new line of

IBM PC-compatible machines that capped an era of profound influence on

the personal computer market.

IBM PS/2 Model 30 adTwenty-five

years ago, IBM announced the Personal System/2 (PS/2), a new line of

IBM PC-compatible machines that capped an era of profound influence on

the personal computer market. Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.That

wasn't a serious problem at first, because those non-IBM machines,

although they ran MS-DOS, could not legally utilize the full suite of

available IBM PC software and hardware add-ons.

Ad from the April 1987 launch, featuring the former cast of the 'MASH' TV show.That

wasn't a serious problem at first, because those non-IBM machines,

although they ran MS-DOS, could not legally utilize the full suite of

available IBM PC software and hardware add-ons. Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.comBut

that lead would not last forever. A profound shift in market leadership

occurred when Compaq released its DeskPro 386, a powerful 1986 PC

compatible that beat IBM to market in using Intel's 80386 CPU. It was an

embarrassing blow to IBM, and Big Blue knew that it had to do something

drastic to solidify its power.

Compaq DeskPro 386 ad. Image: Courtesy of ToplessRobot.comBut

that lead would not last forever. A profound shift in market leadership

occurred when Compaq released its DeskPro 386, a powerful 1986 PC

compatible that beat IBM to market in using Intel's 80386 CPU. It was an

embarrassing blow to IBM, and Big Blue knew that it had to do something

drastic to solidify its power. IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987.

IBM chart explaining the four PS/2 models announced in April 1987. An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.The

built-in mouse port I mentioned earlier is worth noting in more detail.

Each machine in the PS/2 line included a redesigned keyboard port and a

new mouse port, both of which used 6-pin mini-DIN connectors.

An ad describing the IBM Personal System/2.The

built-in mouse port I mentioned earlier is worth noting in more detail.

Each machine in the PS/2 line included a redesigned keyboard port and a

new mouse port, both of which used 6-pin mini-DIN connectors. MCA NIC IBM 83X9648 16-bit-card. Image: Courtesy of Appaloosa, Wikimedia CommonsWith

the PS/2, IBM saw the opportunity to create an entirely new and

improved expansion bus whose design it would strictly control and

license, thus limiting the industry's ability to clone the PS/2 machines

without paying a toll to IBM.

MCA NIC IBM 83X9648 16-bit-card. Image: Courtesy of Appaloosa, Wikimedia CommonsWith

the PS/2, IBM saw the opportunity to create an entirely new and

improved expansion bus whose design it would strictly control and

license, thus limiting the industry's ability to clone the PS/2 machines

without paying a toll to IBM. The high-end Model 80 PS/2As

previously mentioned, IBM planned to release the PS/2 with a completely

new, proprietary operating system called OS/2, which would take

advantage of new features of the 386 CPU in the high-end Model 80,

utilize the built-in mouse port, and also provide a graphical windowing

environment comparable to that of the Apple Macintosh.

The high-end Model 80 PS/2As

previously mentioned, IBM planned to release the PS/2 with a completely

new, proprietary operating system called OS/2, which would take

advantage of new features of the 386 CPU in the high-end Model 80,

utilize the built-in mouse port, and also provide a graphical windowing

environment comparable to that of the Apple Macintosh.